Complex numbers: The complex plane

Polar coordinates

Polar coordinates

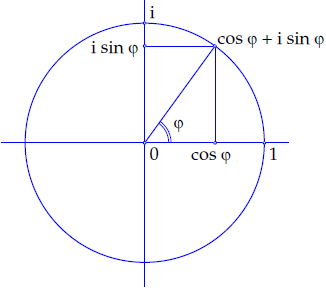

Modulus, argument en polar coordinates Any nonzero complex number \(z=x+\mathrm{i}\,y\) can be written in the form \[z = r\,(\cos\varphi+\mathrm{i}\,\sin\varphi)\] with \[r=|z|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2}\quad\text{and}\quad \varphi=\arg(z)\] Note that \(r\) is the modulus or absolute value of the complex number, and that we call the angle \(\varphi\) the argument of \(z\) call, as with complex numbers on the unit circle . Then \(x=r\,\cos\varphi\) and \(y=r\,\cos\varphi\). We speak of polar coordinates \([r,\varphi]\).

Determination of the argument of a complex number Consider a nonzero complex number \(z=x+\mathrm{i}\,y\) that can be written in the form \(z = r\,(\cos\varphi+\mathrm{i}\,\sin\varphi)\). For the relationship between \(x\), \(y\), \(r\) and \(\varphi\) holds in general: \[\begin{aligned}x=r\,\cos\varphi &,\quad y=r\,\sin\varphi\\ r=\sqrt{x^2+y^2} &,\quad \tan\varphi=\frac{y}{x}\end{aligned}\] Often one concludes that the value of the argument is given by the formula \[\arg(z)=\arctan \left(\frac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{\mathrm{Re}(z)}\right)\tiny.\] This is only true if \(\mathrm{Re}(z)\gt 0\) and in other cases not (check this yourself after for the complex number \(-1-\mathrm{i}\)).

The argument is only determined modulo \(2\pi\). In practice the above equations are sufficient to determine \(\varphi\), but there's a snake in the grass. If \(x=y=0\), then \(\varphi\) is not defined. If \(x=0, y>0\), then \(\varphi =\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi\), and if \(x=0, y<0\), then \(\varphi =-\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi\). In all other cases, you can calculate \(\varphi\) using the arctangent (inverse function of tangent), but you have to into account that the artangent always yields a number between \(-\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi\) and \(\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi\) . If \(x<0\), that is, when the complex number has a negative real part, you have to to add or subtract \(\pi\) to/from the outcome of \(\arctan\left(\dfrac{y}{x}\right)\).

In summary, we have therefore: \[\begin{aligned}\text{if } x=0, y>0\;&\text{then }\varphi=\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi+2k\pi\\ \text{if } x=0, y<0\;&\text{then }\varphi=-\tfrac{1}{2}\!\pi+2k\pi\\ \text{if } x<0, y>0\;&\text{then }\varphi=\arctan\left(\dfrac{y}{x}\right)+\pi+2k\pi\\ \text{if } x<0, y<0\;&\text{then }\varphi=\arctan\left(\dfrac{y}{x}\right)-\pi+2k\pi\\ \text{if } x>0\;&\text{then }\varphi=\arctan\left(\dfrac{y}{x}\right)+2k\pi\end{aligned}\] for some integer \(k\), because the argument is only determined up to an integer multiple of \(2\pi\). We can always select the value in the interval \((-\pi,\pi]\); We then speak of the principal value of the argument and denote this, as with complex numbers on the unit circle, with \(\mathbf{Arg}(z)\). In the above formulation, we have written down these formulas in such a way that the principal value is obtained by omitting the modulo-term with the multiple of \(2\pi\).

For the principal value of the argument of a complex number \(z\) one can also use the following more complicated and difficult to remember formula, without you in case of a complex number with negative real part an arc tangent value needs to adapt:

\[\mathrm{Arg}(z)=\begin{cases}\pi&\text{if } z\text{ lies on the negative real axis}\\ 2\arctan\left(\dfrac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{|z|+\mathrm{Re} (z)}\right)&\text{otherwise }\end{cases}\]

For lovers of mathematics we give a proof of the statement that \(\mathrm{Arg}(z)=2\arctan\left(\dfrac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{|z|+\mathrm{Re} (z)}\right)\) if \(z\) lies not on the negative real axis. We make use of the formula \[\tan\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)=\dfrac{\sin(\alpha)}{1+\cos(\alpha)}\tiny.\] The latter formula follows from the double-angle formulas for trigonometric functions: \[\begin{aligned}\tan\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)&=\dfrac{\sin\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{2}\right)}{\cos\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{2}\right)}\\ &\phantom{uvwxyz}\color{blue}{\text{definition of tangent}}\\ &=\dfrac{2\sin\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{2}\right)\cdot\cos\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{2}\right)}{2\cos^2\left(\dfrac{\alpha}{2}\right)}\\ &\phantom{uvwxyz}\color{blue}{\text{numerator and denominator multiplied by }2\cos\left(\frac{\alpha}{2}\right)}\\ &=\dfrac{\sin\left({\alpha}\right)}{1+\cos\left(\alpha\right)}\\ &\phantom{uvwxyz}\color{blue}{\cos(2x) =2\cos(x)^2-1\text{ and }\sin(2x)=2\sin(x)\cdot\cos(x)}\\ \end{aligned}\]

\(\varphi=\arg(z)\) is determined by the conditions \[\begin{aligned}\cos(\varphi)&=\dfrac{\mathrm{Re}(z)}{|z|}\\ \sin(\varphi)&=\dfrac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{|z|}\\ \varphi&\in (-\pi,\pi]\tiny.\end{aligned}\] From the first two conditions follows \[\tan\left(\frac{\varphi}{2}\right)=\frac{\sin(\varphi)}{1+\cos(\varphi)}=\dfrac{ \dfrac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{|z|} }{1+\dfrac{\mathrm{Re}(z)}{|z|}}=\dfrac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{|z|+\mathrm{Re}(z)}\tiny.\] From the third condition follows \(\dfrac{\varphi}{2}\in(-\pi,\pi]\).

According to the theory of inverse trigonometric functions, the function \(\arctan\) is the inverse of \(\tan\) on \(-\tfrac{1}{2}\pi,\tfrac{1}{2}\pi]\). Therefore holds for \(\varphi\ne\pi\) , that is to say, for \(z\) not on the negative real axis: \[\varphi = 2\arctan\left(\tan\left(\dfrac{\varphi}{2}\right)\right)=2\arctan\left(\dfrac{\Im(z)}{|z|+\Re(z)}\right)\tiny.\]

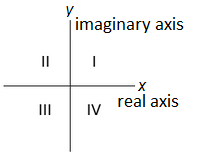

Calculation Schedule for the principle value of the argument The quadrants of the complex plane are numbered in the figure below.

The following algorithms show how to compute the principal value \(\mathrm{Arg}(z)\) of the complex number \(z=x+y\,\ii\) on the basis of the position of the corresponding point \((x,y)\) in the complex plane. \[\begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \hline \textit{quadrant} & \textit{sign of }x\textit{ and }y & \mathrm{Arg}(z)\\ \hline\hline \mathrm{I} & x>0,\quad y>0 & \arctan(y/x) \\ \hline \mathrm{II} & x<0,\quad y>0 & \pi+\arctan(y/x) \\ \hline \mathrm{III} & x<0,\quad y<0 & -\pi+ \arctan(y/x)\\ \hline \mathrm{IV} & x>0,\quad y<0 & \arctan(y/x) \\ \hline \end{array}\] For points on the edges of the quadrants you can use the following scheme. \[\begin{array}{|c|c|c|c|} \hline \textit{edge} & \textit{type of complex number }z & \textit{conditions for }x\textit{ and }y & \mathrm{Arg}(z)\\ \hline\hline \mathrm{IV/I} & \text{real positive} & x>0,\quad y=0 & 0 \\ \hline \mathrm{I/II} & \text{pure imaginary with Im}(z)>0 & x=0,\quad y>0 & \tfrac{1}{2}\pi \\ \hline \mathrm{II/III} & \text{real positive} & x<0,\quad y=0 & \pi\\ \hline \mathrm{III/IV} & \text{pure imaginary with Im}(z)<0 & x=0,\quad y<0 & -\tfrac{1}{2}\pi\\ \hline \mathrm{origin} & \text{zero}& x=0,\quad y=0 & \text{undetermined} \\ \hline \end{array}\]

Polar form The notation with imaginary \(e\)-powers gives \[z=r\,e^{\,\mathrm{i}\,\varphi}\] It is called the polar form of the complex number \(z\).

\(\phantom{x}\)

Look at enough examples of conversions between standard form and polar form of a complex number.

The \(r\) coordinate is equal to the absolute value of \(z\); to calculate this value you just need to determine the real and imaginary part of \(z\): \[\begin{aligned}\mathrm{Re}(z)&= -1\\ \mathrm{Im}(z)&= -1\\ \\ r&=|z|\\ &= \sqrt{\bigl(\mathrm{Re}(z)\bigr)^2+\bigl(\mathrm{Im}(z)\bigr)^2} \\ &=\sqrt{\bigl(-1\bigr)^2+\bigl(-1\bigr)^2}\\ &=\sqrt{2}\end{aligned}\] The argument of \(z\), denoted as \(\varphi\), you get from the following two equations: \[\cos(\varphi)= \frac{\mathrm{Re}(z)}{r}\qquad\mathrm{and}\qquad \sin(\varphi)= \frac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{r}\] In this case \[\cos(\varphi)= \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}}=-\tfrac{1}{2}\!\sqrt{2}\qquad\mathrm{and}\qquad \sin(\varphi)= \frac{-1}{\sqrt{2}}=-\tfrac{1}{2}\!\sqrt{2}\] From the last two equations and the position of the complex number in the complex plane you derive the principal value of the argument: \[\varphi=-\tfrac{3}{4}\pi\] Let op dat in dit geval \(\varphi\ne \arctan\Bigl(\frac{\mathrm{Im}(z)}{\mathrm{Re}(z)}\Bigr)\) omdat \(\arctan(1)=\tfrac{1}{4}\pi\).

Je moet bij deze waarde zelf \(\pi\) aftrekken om de hoofdwaarde van het argument van \(z\) te vinden.

See the figure below for a geometric interpretation of the transition from the standard form of a complex number to that of polar coordinates. The complex number is shown in blue. The absolute value #r# and the argument #\varphi# are drawn in red.

Straight lines in terms of polar coordinates We can use the argument of a complex number to describe straight lines in the plane using complex numbers. This is done as follows. Suppose \(\varphi\) is a real number and \(w=a+b\,\mathrm{i}\) is an arbitrary complex number with real part \(a\) and imaginary \(b\). Then, the line through the point \(\rv{a,b}\) with slope \(\tan(\varphi)\) is not only given by the equation \[\sin(\varphi)\cdot (x-a)-\cos(\varphi)\cdot (y-a)=0\] but also by the following complex equation (with unknown \(z\)): \[\arg(z-w) = \varphi\quad (\text{mod }\pi)\]

Mathcentre videos

Modulus and Argument (11:02)

Polar Form (11:29)